By: Kenichiro Yagi, BS, RVT, VTS (ECC, SAIM)

Canine parvovirus (CPV) infections cause severe gastroenteritis, lead to dehydration, shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation, bacterial translocation and sepsis when left untreated. With aggressive treatment, the mortality rate can be reduced to between 0% and 30% from 90%. Therapeutic options in addition to fluid and pharmacologic therapy speeding gastrointestinal recovery is desirable to reduce patient mortality and morbidity, as well as financial strain to the clients for prolonged aggressive treatment. Use of elaborate treatment options such as oseltamivir (Tamiflu), interferon omega, recombinant bactericidal proteins, equine lipopolysaccharide antitoxin, human recombinant factors, and antibody rich plasma have not shown promising results. One simple to implement, therapeutic option that makes a significant difference in survival chance is enteral feeding started within hours of admission, even when vomiting.

Wait, what? Feed a patient that is vomiting?

I know, it sounds crazy, right? There are many arguments for withholding food from patients that are vomiting, and the standard course of treatment involves NPO (nil per os, or no food or water from the oral route) for a day or two, and then gradually introducing small amount of easily digestible food.

Withholding food is thought to be beneficial because:

- It allows the bowel to rest (who wants to digest and absorb with irritated guts, anyways?).

- Vomiting is less likely to occur on an empty stomach, and is thought to reduce chances of aspiration.

- Diets containing fat and fiber may also promote emesis; the opposite of what we are trying to accomplish.

- The guts are not working so well allowing undigested food to pass into the intestines. This supports (a) bacterial proliferation and (b) osmotic action pulling water into the intestinal lumen, exacerbating diarrhea.

With all these issues caused by feeding a patient with gastroenteritis, why would any sane person recommend instituting early enteral nutrition? Good question.

#1 The guts aren’t really resting

Fasting is associated with “hunger pains”, which arise from intense peristaltic contractions migrating down from the pylorus to the ileum. The motor activity is reduced by the presence of nutrients in the intestinal lumen, providing more rest compared to when fasted. So fasting does not actually allow the guts to rest, and it also causes pain.

#2 Vomiting can occur, but usually subsides

A study observed an increased frequency of vomiting in patients with hemorrhagic gastroenteritis upon introduction of small feedings. However, the frequency in vomiting decreased on day 2. Feeding creates a prokinetic effect, and reduces emesis, leading to an overall shortening of the time required for the patient to stop vomiting. The presence of food in the gastrointestinal lumen also decreases insult to the mucosa from toxins, reducing vomiting. Remember those “take with food” labels on some medication?

#3 Diets containing fat and fiber can cause vomiting, but can be moderated

Food high in fat and soluble fibers and large volume feedings can indeed increase chances of vomiting. Maldigestion and gastrointestinal distention stimulates vomiting. Small, frequent feedings are recommended to reduce gastric acid release, leading to reduced vomiting. In many cases, employment of anti-emetic drugs help in preventing vomiting, allowing earlier enteral nutrition. Adequate antiemesis is especially important for inappetant patients requiring placement of NE or NG tubes.

#4a Presence of food thwarts bacteria

Undigested food being present in the intestinal lumen does increase nutritional resources for microorganisms leading to bacterial proliferation. However, feeding increases levels of volatile fatty acids such as butyrate and porprionate, reducing the population of bacteria sensitive to acidic environments (Campylobacter and Clostridium spp.). The presence of food helps maintain enteric barriers, preventing bacterial translocation (movement of bacteria from the guts into the blood stream) and subsequent sepsis.

#4b Undigested food does not contribute to osmotic diarrhea

Diarrhea in dogs is attributed to unabsorbed nutrients and endogenously derived osmotic elements instead of osmotic pressure created by undigested food. Insult to the intestinal mucosa preventing absorption of water and increased effusion through leaky blood vessels (increased vascular permeability) is alleviated with enteral nutrition, which helps reduce diarrhea when compared to a fasted state.

#5 Other positive effects of feeding

Fasting causes a plethora of negative effects that outweigh the small benefits it may have. Fasting causes reduced expression of digestive enzymes, impairing digestive function when food is reintroduced. Presence of nutrients reduces inflammation by inhibiting expression of adhesion molecules, preventing activation of neutrophils which contribute to mucosal damage and impair immune response. Malnutrition leads to protein, essential fatty acid, mineral and vitamin deficiencies preventing healthy turnover of gastrointestinal mucosa. Feeding leads to faster intestinal recovery, even when compared to parenteral nutrition, indicating benefits of passive luminal nutrition. Feed those guts!

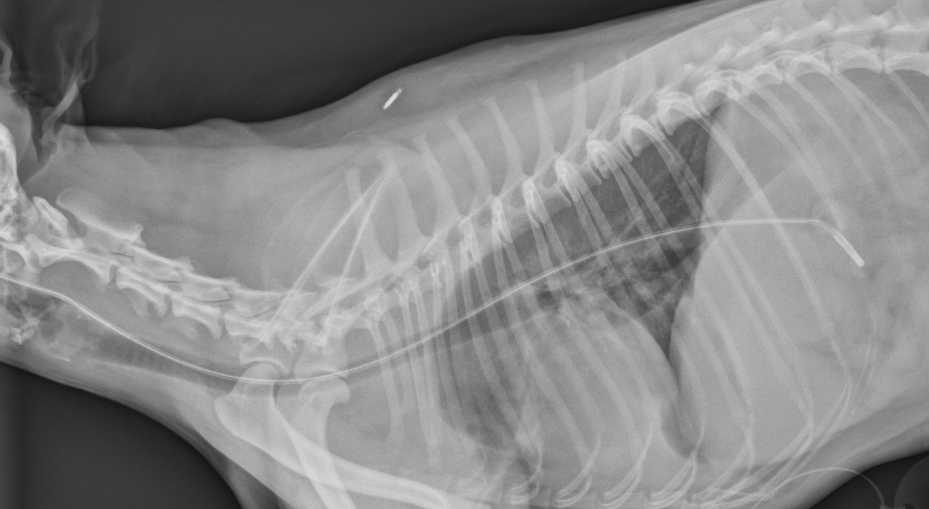

Providing Enteral Nutrition with NE or NG tubes

As long as the patient’s vomiting is controlled, a nasoesophageal (NE) or nasogastric (NG) tube is an easy method to provide enteral nutrition. These nasoenteric tubes are useful in short term feeding (1-10 days) in patients with a functional gastrointestinal tract. Placement can be achieved often without sedation, or with light sedation when required, perfect for critical care patients.

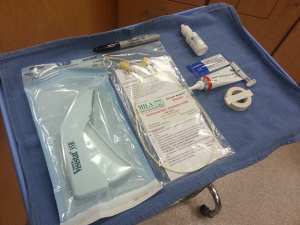

Required Supplies

- Local anesthetic drops (e.g. proparacaine)

- Local anesthetic or lubricating jelly

- Permanent marker to note intended placement length

- Skin stapler or suture

- ½ inch tape (If using skin staples)

- Feeding tube (appropriate size/length)

- E-collar

- Radiograph request (confirm placement!)

NG tubes should be opted for placement when gastric motility is in question, allowing for measurement of residual gastric content. NE tubes will prevent measurement of gastric content but is useful in routine feeding. The narrow diameter makes use of canned food virtually impossible, but many liquid diets are commercially available. Use is contraindicated in patients that are vomiting, comatose, have respiratory distress, lack a gag reflex, or suffering from trauma to the nasal cavity. NE and NG tube placement is a skill every technician can master in short order.

Treating Canine Parvovirus

When reading literature regarding the treatment of canine parvovirus infections, all of them agree that aggressive fluid therapy, electrolyte balance, and pharmacologic interventions are key factor in successful treatment. Some sources will advocate for withholding of food and water until vomiting has stopped. Our current knowledge tells us early enteral nutrition even when the patient is vomiting, will help speed recovery, increase body weight, and improve clinical signs of inappetance, vomiting and diarrhea.

A groundbreaking antibiotic therapy (parvoONE by Avianax) reducing the mortality rate in dogs with canine parvovirus infections to 15% was recently reported to be undergoing field trial and planned to be released to the market in Spring 2015. We should await confirmation of the efficacy of this drug, and keep in mind the low mortality rate is a result of combination of supportive care and the new therapy. Be sure to advocate for early enteral nutrition in your next parvoviral enteritis case!

*If any of this information was useful or you would like to see similar content, “LIKE” the Pet ED Veterinary Education and Training Resources Facebook page and subscribe on the HOME page of the PetED website to receive upcoming newsletters and news.