By Vickie Byard, CVT, VTS (Dentistry)

I didn’t think I was going to get anything to share with you today, but the educational gods smiled sweetly on us.

Today, a 5 month old Shih-tzu mix was admitted to the hospital to be spayed. She was very nervous and the most complete oral examination was only possible once she was anesthetized. With careful inspection, one of the veterinarians noted that both of the lower third molars were missing. Considering that this was a puppy and she had never had dentistry before, the good doctor asked me to get permission from the client for two intraoral X-rays of these areas.

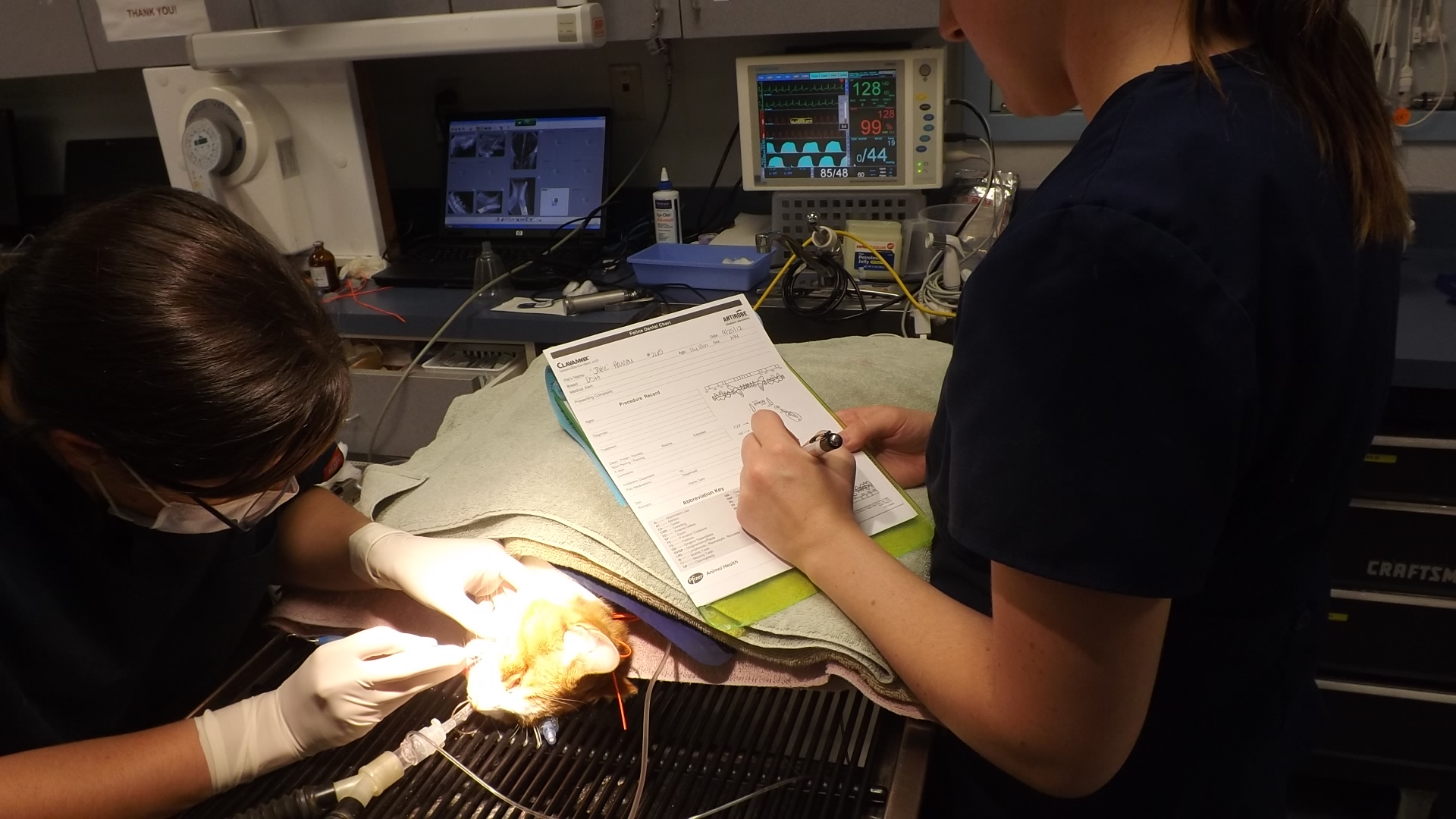

As you can see in the photo, it seems like there could not possibly be room for yet another tooth to develop. You can also see the lovely green fingernail polish of our incredible anesthesia technician (who by the way was quite annoyed with my sneaking in this clinical photo while she was maintaining the warmth of her patient during recovery….we paparazzi are annoying).

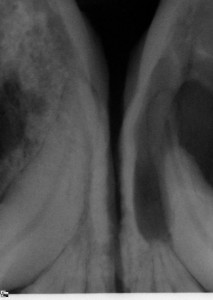

Next the radiograph, as those of you that have come to expect will be fun and informative:

So, what we see in this X-ray is a misdirected, impacted left lower third molar. The apex of the tooth is still open due to the patient’s youth but you can appreciate a radiolucent halo around the crown of the tooth. This is why we check for impacted teeth. This is probably already forming a dentigerous cyst which may already be negatively impacting the health of the single rooted left lower second molar.

So, to understand what a dentigerous cyst is, we need to understand the embryology of the tooth. When the tooth bud forms the enamel, there is a membrane that encases the crown and attaches at the junction of the enamel and the developing tooth root. When the tooth is unable, for whatever reason, to erupt through the bone and tough gingival (gum) tissue, that sac never has an opportunity to rupture. As we know with most cystic membranes, they tend to pull fluid into the interior of the sac. With time, the cyst enlarges and through pressure, these dentigerous cysts can destroy large portions of the dental arcade.

This last X-ray is an example of the kind of damage possible when these odontogenic cysts are not investigated. Most patients show no discomfort and often no clinical evidence of the presence of a cyst. This older patient’s (actually only a 4 year old Boxer) mandible is greatly weakened by the destruction of the cortical bone making jaw fracture a real possibility….and correction was VERY expensive.

As you may know, I do not work with a board certified veterinary dentist. The value of this X-ray is tri-fold:

1. We can appreciate that this will be difficult. There is little room with which to work.

2. This tooth is deep in the bone

3. A specialist should evaluate and decide whether or not it is wise to sacrifice the second molar as well.

There is enough periodontal work for general practices to stay busy with forever. I can’t recommend strongly enough for practices to establish a wonderful relationship with the veterinary dental specialist close to you. In the long run, you will appreciate having that expertise behind you.

So, the lessons I would like everyone to take home are these:

- Count teeth and radiograph all areas where teeth are missing and there is no record of an extraction.

- These can occur anywhere in the mouth and with any breed.

- These are easiest to treat and correct when first developing.

- If you have never seen one, you just haven’t yet begun to look. They are there.

- Catching these early is great wellness care.

And…if you are a veterinary technician and your practice has not come across these from time to time, this is a great way to bring new information to your practice and play a part in the incredible service provided by your practice.